CBPP Statement: June 6, 2014

For Immediate Release

Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the May Employment Report

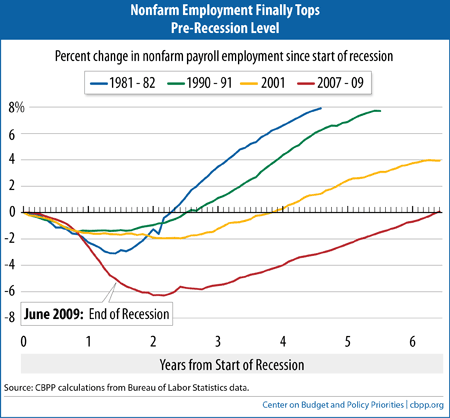

More than six years after the Great Recession and the worst jobs slump since

the 1930s began, todayfs jobs report shows that payroll employment has finally

topped its level at the start of the recession (see chart). Still, with

essentially no net job growth since December 2007 but a growing working-age

population, many more people today want to work but donft have a job.

Not all of these people show up in the official unemployment rate. Thatfs

because some of them who want a job arenft actively looking for one, for any

one of several reasons. Some are discouraged by their prospects of

finding a job. Others have decided that, until job prospects improve,

they could better spend their time staying home to care for young children

rather than pay for child care, doing home repairs rather than pay someone to

do them, or taking courses at the local community college to improve their

future earnings prospects. These people are not classified as unemployed

because they are not actively looking for work and therefore not in the labor

force.

Stronger demand for goods and services and the faster job creation that will

result from it is the key to lowering unemployment and enticing people back

into the labor force. Hopeful signs suggest that the slide in labor

force participation that has characterized this weak recovery may be ending,

but we still have a long way to go before we return to full employment with

normal labor force participation.

Stronger demand growth and faster job creation also may be the last best

hope for the long-term unemployed (those looking for work for six months or

longer), who research suggests donft look much different from other unemployed

workers — except that they lost their job at a particularly bad time for

finding a new one and then faced discrimination by prospective employers for

having been unemployed so long. Policymakers abandoned the long-term

unemployed, first when they let emergency federal unemployment insurance (UI)

expire at the end of last year and then when the House refused to even consider

the bipartisan Senate compromise that would have extended those benefits

through the end of last month.

Emergency UI not only provides needed financial support to jobless workers

and their families, but also keeps long-term unemployed workers in the labor

force looking for work rather than dropping out. On a bang-for-the-buck

basis, itfs also one of the best ways to stimulate demand and strengthen the

job market. That policymakers let it lapse was a tragedy.

About the May Jobs Report

Employers reported solid payroll growth in May. In the separate

household survey, the labor force grew moderately and the unemployment rate,

labor force participation rate, and percentage of the population with a job

were essentially unchanged.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 217,000 jobs in May but

the Bureau of Labor Statistics revised job growth in the previous two months

downward by a total of 6,000 jobs. Private employers added 216,000 jobs

in May, while overall government employment rose by 1,000. Federal

government employment fell by 5,000, state government fell by 5,000, and

local government rose by 11,000.

- This is the 51st straight month of private-sector job creation, with

payrolls growing by 9.4 million jobs (a pace of 184,000 jobs a month) since

February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has

grown by 8.8 million jobs over the same period, or 173,000 a month.

Total government jobs fell by 599,000 over this period, dominated by a

loss of 348,000 local government jobs.

- The job losses incurred in the Great Recession have been erased.

There are now 620,000 more jobs on private payrolls and 113,000 more jobs on

total payrolls than there were at the start of the recession in December

2007. Because the working-age population has grown over the past six

and a half years, however, the number of jobs remains far short of the number

of jobs needed to restore full employment. The pace of job creation so

far this year (214,000 jobs a month) is the highest five-month average in

over a year, and, if maintained, would gradually restore normal labor market

conditions. Faster job growth would clearly be better, though.

- The unemployment rate held steady at 6.3 percent in May, and 9.8 million

people were unemployed. The unemployment rate was 5.4 percent for

whites (1.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession),

11.5 percent for African Americans (2.5 percentage points higher than at the

start of the recession), and 7.7 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (1.4

percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession drove many people out of the labor force, and lack of job

opportunities in the ongoing jobs slump kept many potential jobseekers on the

sidelines and not counted in the official unemployment rate. Although

the decline in labor force participation appears to have bottomed out, the

labor force participation rate (the share of the population aged 16 and over

either working or actively looking for work) remained at 62.8 percent in

May. It hasnft been lower since 1978. The labor force grew by

192,000 in May, the number of employed by 145,000, and the number of

unemployed by 46,000.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession

from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and

has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 58.9 percent in May,

slightly above its 2013 average of 58.6 percent.

- The Labor Departmentfs most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate

measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from

looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working

part time because they canft find full-time jobs — edged down to 12.2 percent

in May. Thatfs down from its all-time high of 17.2 percent in April

2010 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 3.4 percentage points higher

than at the start of the recession. By that measure, about 19 million

people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Roughly a

third (34.6 percent) of the 9.8 million people who are unemployed — 3.4

million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer.

These long-term unemployed represent 2.2 percent of the labor force.

Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the

past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June

1983, early in the recovery from the 1981-82 recession. By the end of

the first year of the recovery from that recession, however, the long-term

unemployment rate had dropped below 2 percent.

# # #

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit,

nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research

and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is

supported primarily by foundation grants.